Re-housing is a housing initiative housed at the University of Toronto. It’s a collaboration between academia, which is where I come from, and a practicing architectural firm in Toronto: LGA architectural partners. This collaboration brings together speculative research methods and practical experience to think innovatively about real-world problems facing cities.

This project looks at adding incremental new density to single-family neighborhoods, the pattern that makes up a majority of land area in Northern America.

1 What is the Yellowbelt

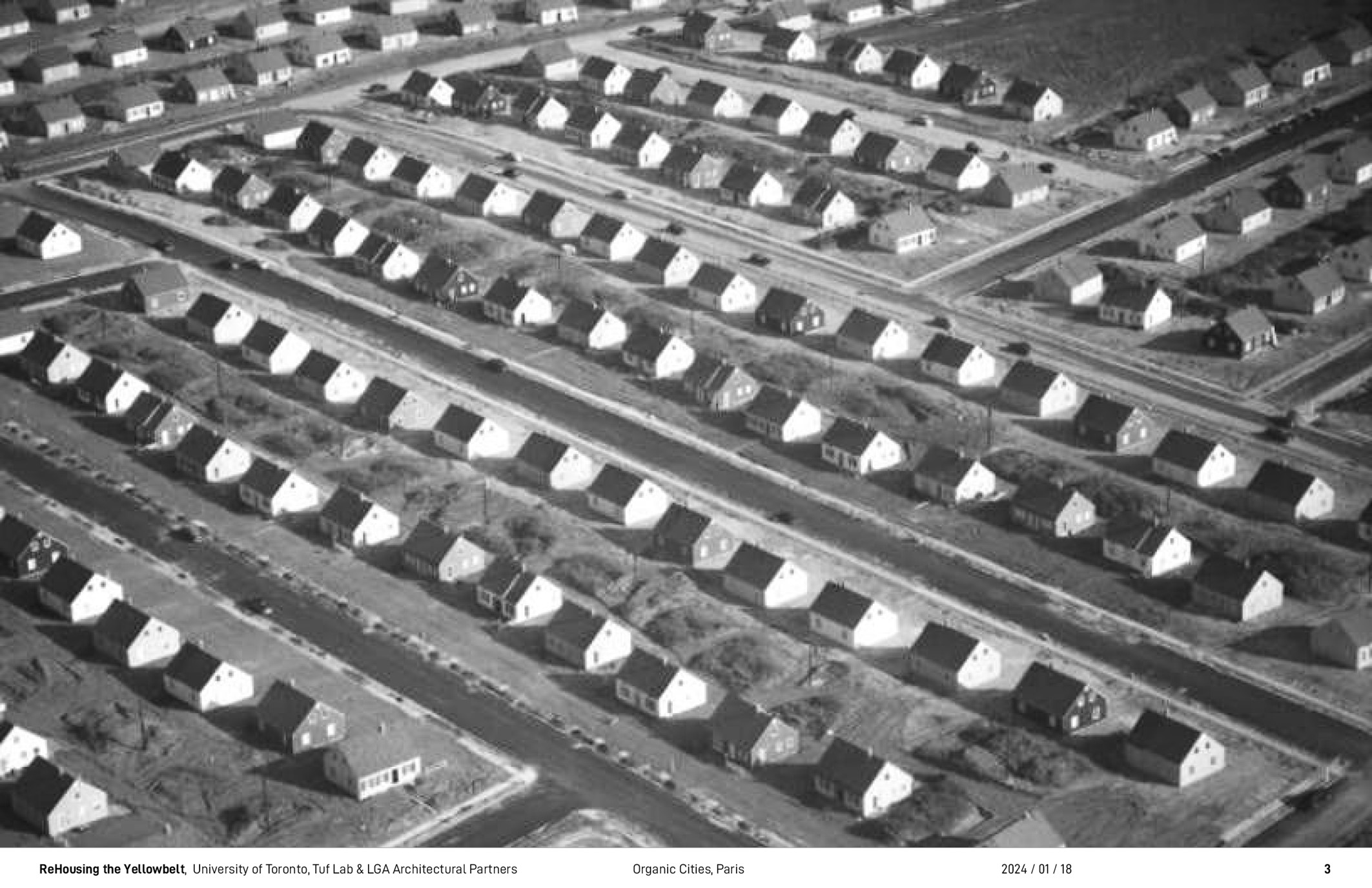

We are familiar with images like these: this is Levittown. It was one of the first suburbs that was built outside of New York City. This pattern of urbanization, as was mentioned earlier, has expanded to constitute a majority of land area and almost all North American urban areas.

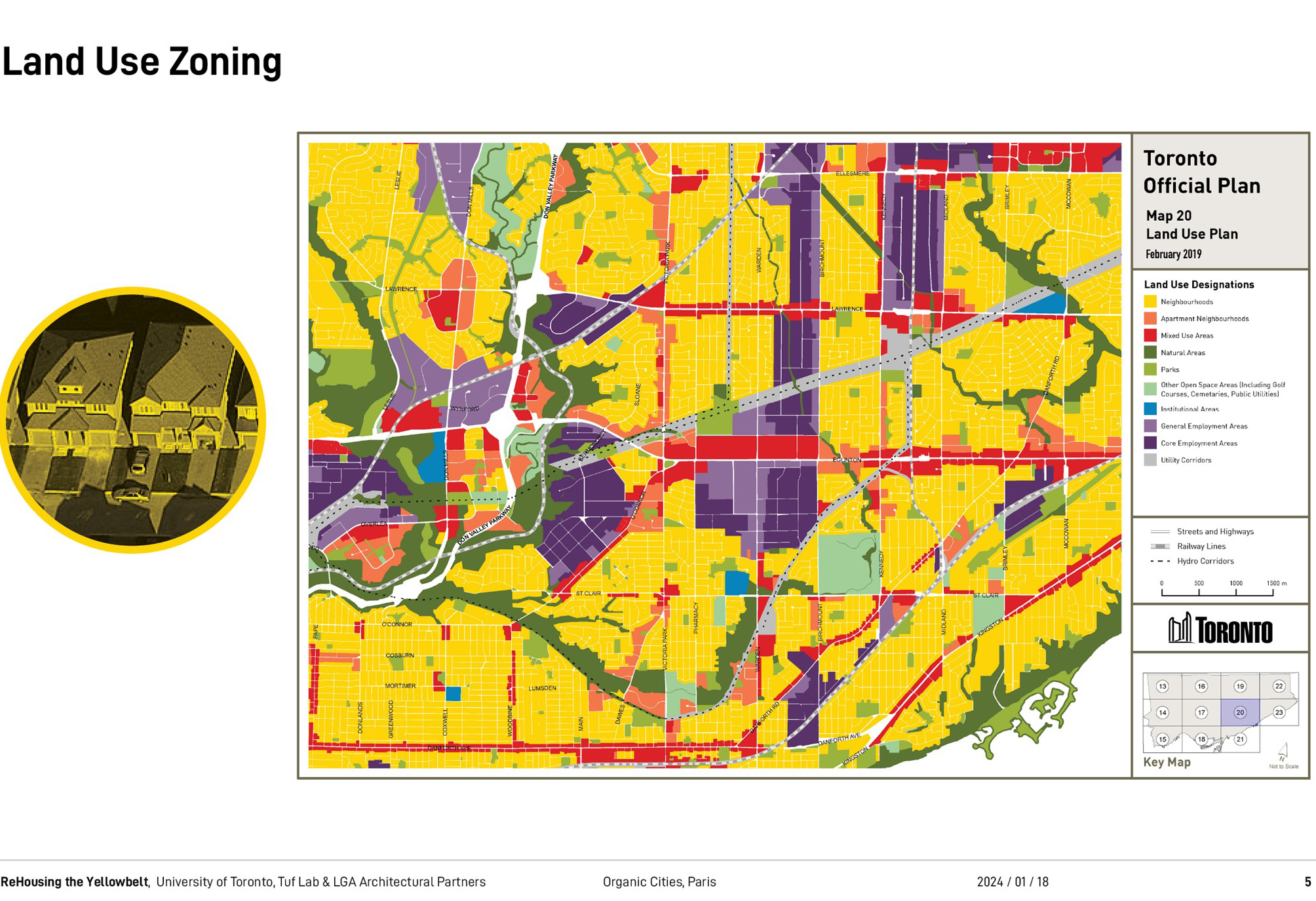

The yellow belt as the title of my lecture notes is a result of land use zoning. I imagine most of you are familiar with this, where we as urban planners designate parts of the city by use. Yellow is the color for single-family residential uses, hence the yellow belt, and by law one is only allowed to have one family per parcel of land.

The other tool that perhaps is a little bit less familiar is the neighborhood unit. This was invented in 1929 by Clarence Perry. It’s a diagram for how to organize land use in physical space. Commercial corridors enclose the neighborhood unit where single-family dwellings are gathered around a public school located in the middle, and so this is so kids can walk to school without crossing streets.

That diagram was initially based on the ideal of the Garden City in England where these little towns or neighborhoods were supposed to be walkable and linked to the city by higher order transit. That diagram was adapted to the North American context, scaled up, abstracted, local retail was replaced with shopping malls, and it’s become quite different from as it was initially imagined.

The 2.2 kilometer dimension corresponds to the Colonial Land Survey systems that organize much of North American urbanization. In the USA, it refers to Thomas Jefferson’s land ordinance survey. In Toronto and in other parts of Canada, we have similar systems. This kind of dimensional organization allowed for the rapid deployment of the neighborhood unit, and it has come to constitute much of what we now refer to as urban sprawl. We don’t like this, we complain about it, it drives car ownership, and it defines much of the kind of debate about how we need to make cities in North America. Generally, we need to get rid of this, and we need to replace it with something better, walkable urban areas, it is hard to argue with that.

2 Mapping Toronto’s Yellowbelt

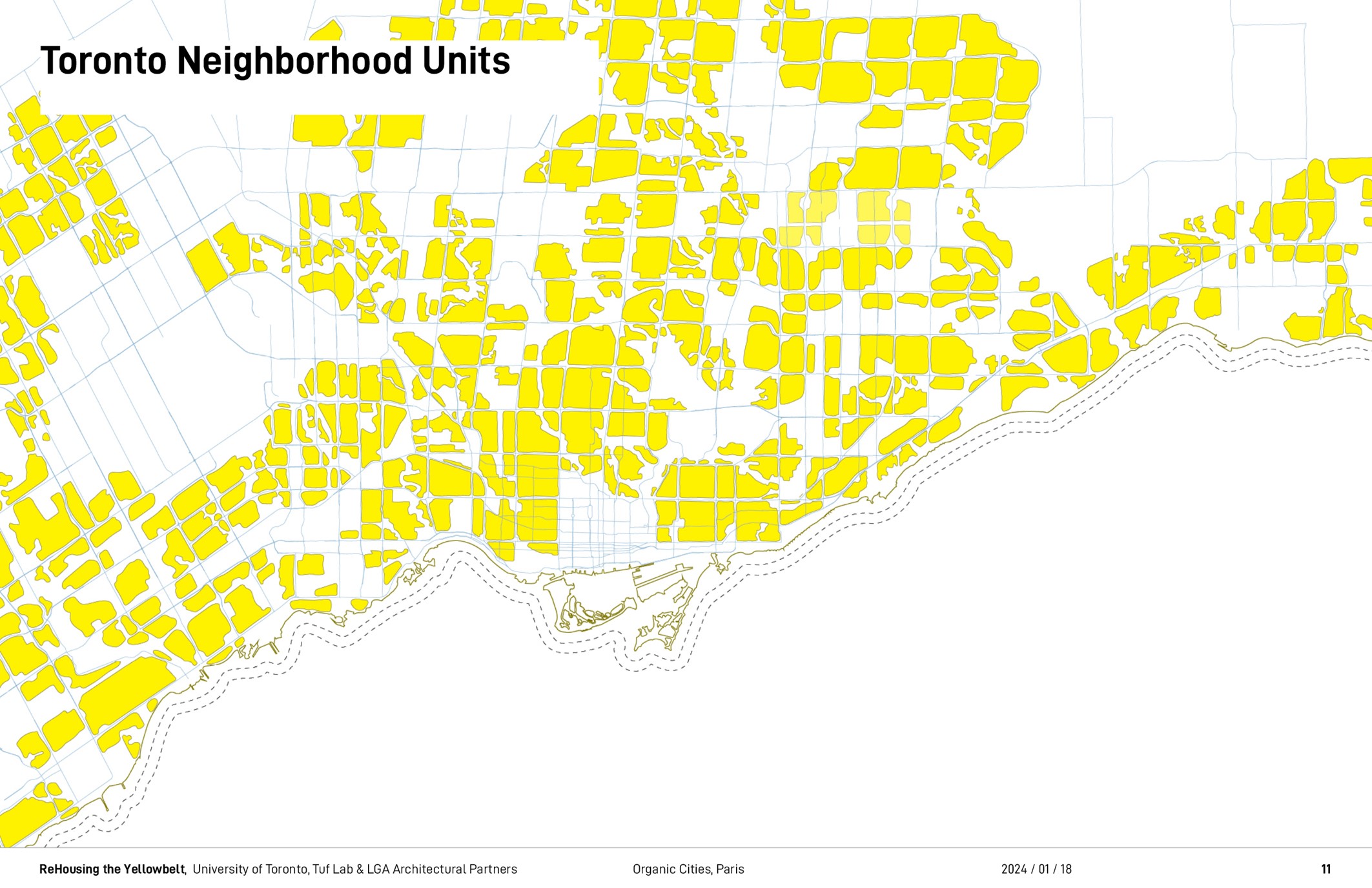

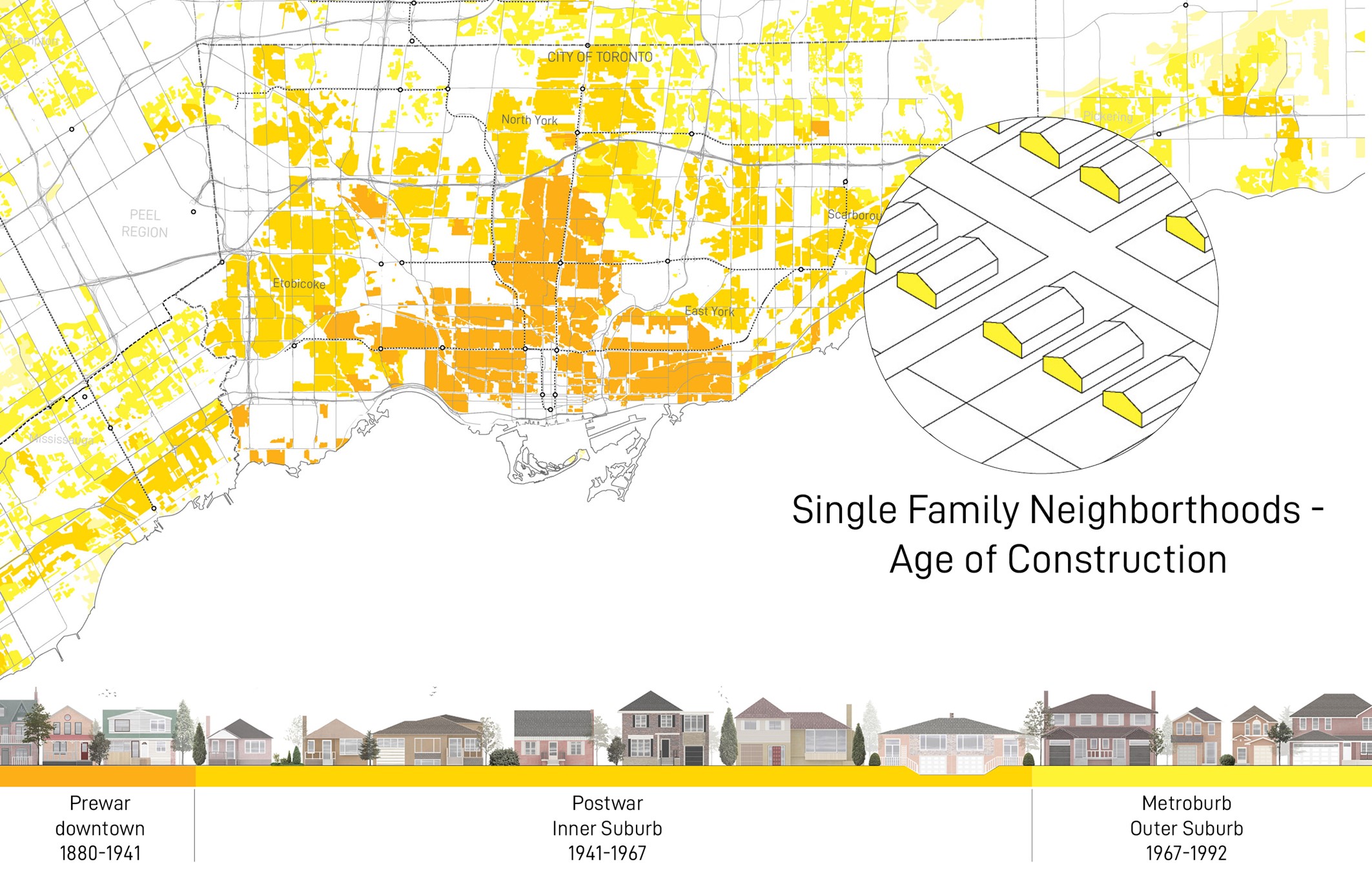

Here is a map we made of Toronto’s neighborhood units. You can see they are organized by the arterial street pattern. To provide some context, Toronto is located along Lake Ontario at the border of the USA and Canada. Indeed Toronto proper is part of a much larger land area called the Greater Toronto Area, a nebulous term we use in North America to describe urban agglomeration.

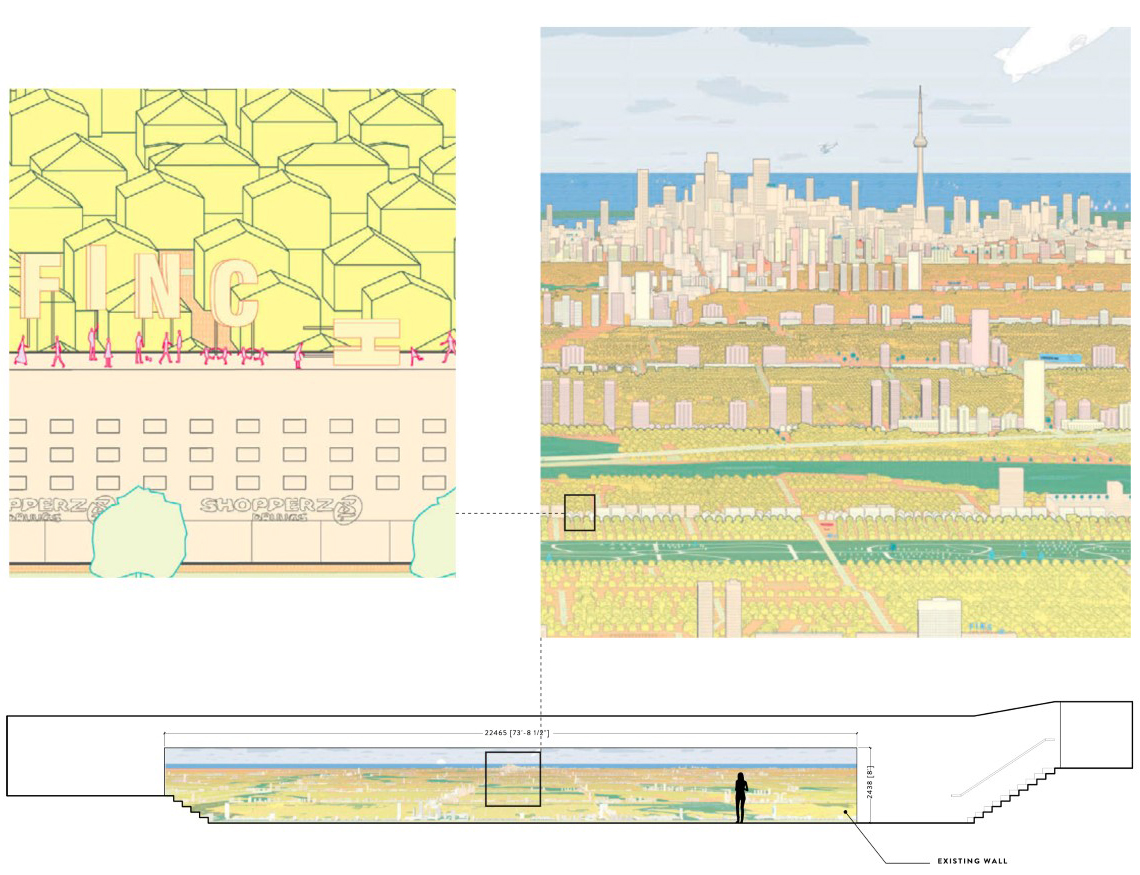

In the Greater Toronto Area, over 60% of the land area is for single-family dwellings. This encompasses some 2 million single-family homes on 95’000 hectares of land. The problem is that, as our population increases, we are relying on less than half of our land area to create housing for a growing population. This has driven up costs, is cause for speculation, and a gross undersupply of housing. We made this 20 meter long drawing to visualize the vastness of single family neighborhoods of the Greater Toronto Area.

We modeled every home in the region and showed the drawing with other media as part of an exhibition that we had at the University of Toronto. Our goal was to encourage people to think differently about North American urban regions, to understand that it is not made up of just the downtown, but includes vast landscapes beyond.

As academics and professionals, we have tended to criticize suburban landscape as a bland space of privilege and wealth. However, there has been a demographic shift in the Northern American suburban conditions. It used to be that low-income residents lived in the city center, where wealthy residents moved to the suburbs. That condition has progressively changed over the last 40 years. Now a majority of our low-income residents, immigrants, and racialized minorities now live in suburban areas and are trying to kind of make live in this landscape that was not necessarily designed for them. There is a lot more to say about this, but for the sake of brevity, I’ll provide an example of this condition from Toronto that is particularly relevant to the current work.

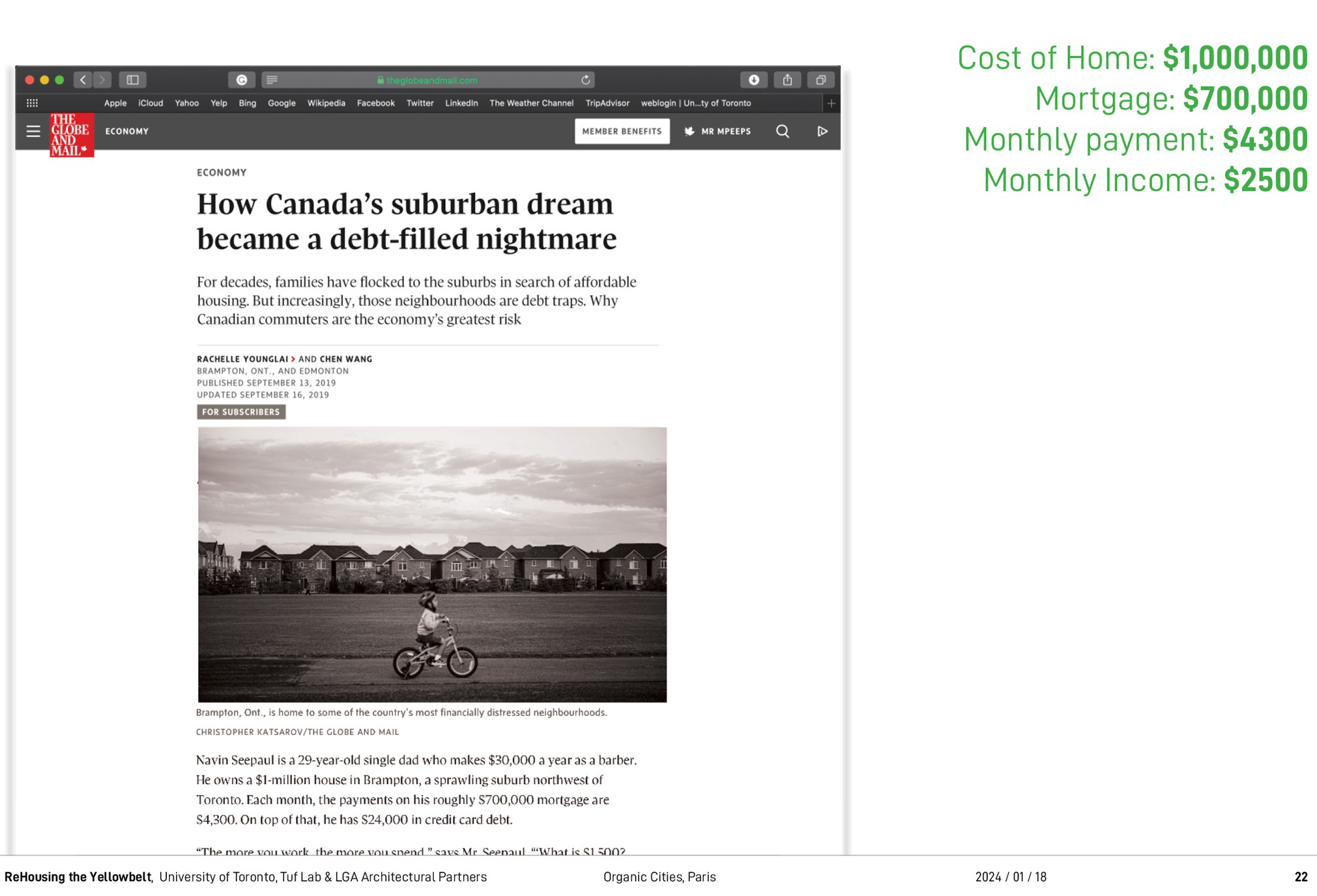

3 An example of a “citizen-developer”

This is an article about Naveen Sipal. He is a 29 years old single father and hairstylist. He bought a million-dollar home with a barber’s salary in a suburban area outside of Toronto called Brampton. His mortgage is $700’000. His monthly payment is 4’300 dollars, and this constitutes 172 percent of his income monthly. Economists, planners often say that number should be 30 percent. In order to cover the cost of his mortgage, he created a rental unit in his basement, charged $2’000 for that and rents out unused bedrooms with Airbnb to generate additional income. This income helps Naveen cover his debts and expenses. Here, economic pressure is driving a new kind of housing creation. One not necessarily motivated by large developers creating big buildings to house large numbers of people, and therefore the money being extracted from the collective to a third party.

But instead, this is a new kind of economy where the homeowner, the owner-occupant, is creating housing and is keeping that wealth on the site where it is drawn from. Because this type of housing does not need to provide income to support a development or property management business, it is possible, in an ideal world, to offer lower rents. While the circumstances that drive this kind of housing creation are not ideal, such as for Navin Sipaul, the actions taken by these individuals represent a form of ingenuity and organic city making that we think holds potential for new housing creation in Northern American suburbs. We describe such individuals as citizen developers, a group of individuals for whom the creation of housing is a means to housing security.

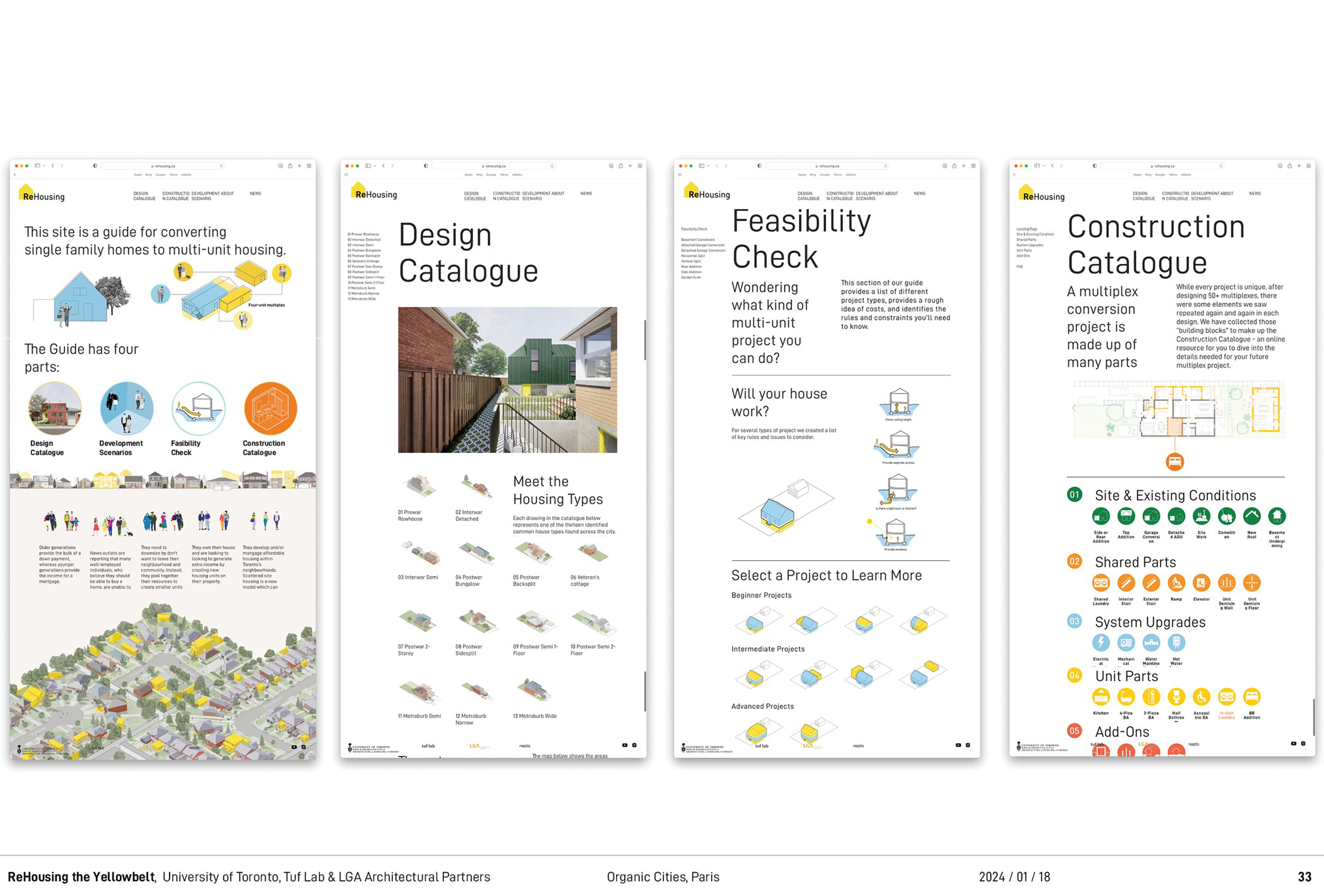

4 Our website (Re-Housing)

Our website, Re-Housing, is intended to support citizen developers and to help them better understand what it takes to convert a home to a multiplex. We explain to zoning codes, building regulations, and other kinds of barriers that are otherwise difficult for non-professionals to access. The website is really intended to support non-professionals. We used cartoon-like graphics to make things easy to understand. We used straightforward text to try to explain complex ideas such as zoning code in a way that was easy for non-professionals to access.

5 Our research

My research uses design and analytical knowledge about physical space to impact policy making. In 2018, new multiplex zoning policy was initiated by the City of Toronto. We studied the new policy and tried to identify gaps or shortcomings. We identified two such gaps.

On one hand, the policy was focused primarily on new construction. We thought that there should also be a focus on renovating existing homes to multi-unit housing. Reusing existing buildings is a carbon positive and potentially lower cost way to create housing, however, there is a lack of systemic knowledge about this process. And this lack of systemization means this kind of project is not necessarily scalable.

Secondly, the multiplex policy was focused on the city center, where the most of our wealthiest residents live and tended to exclude the vast range of urban area that constitutes the expanse of the urban region. We responded to this knowledge by creating a research framework for studying different neighborhoods from across the urban region to understand the diversity of housing types.

This map shows these different areas.

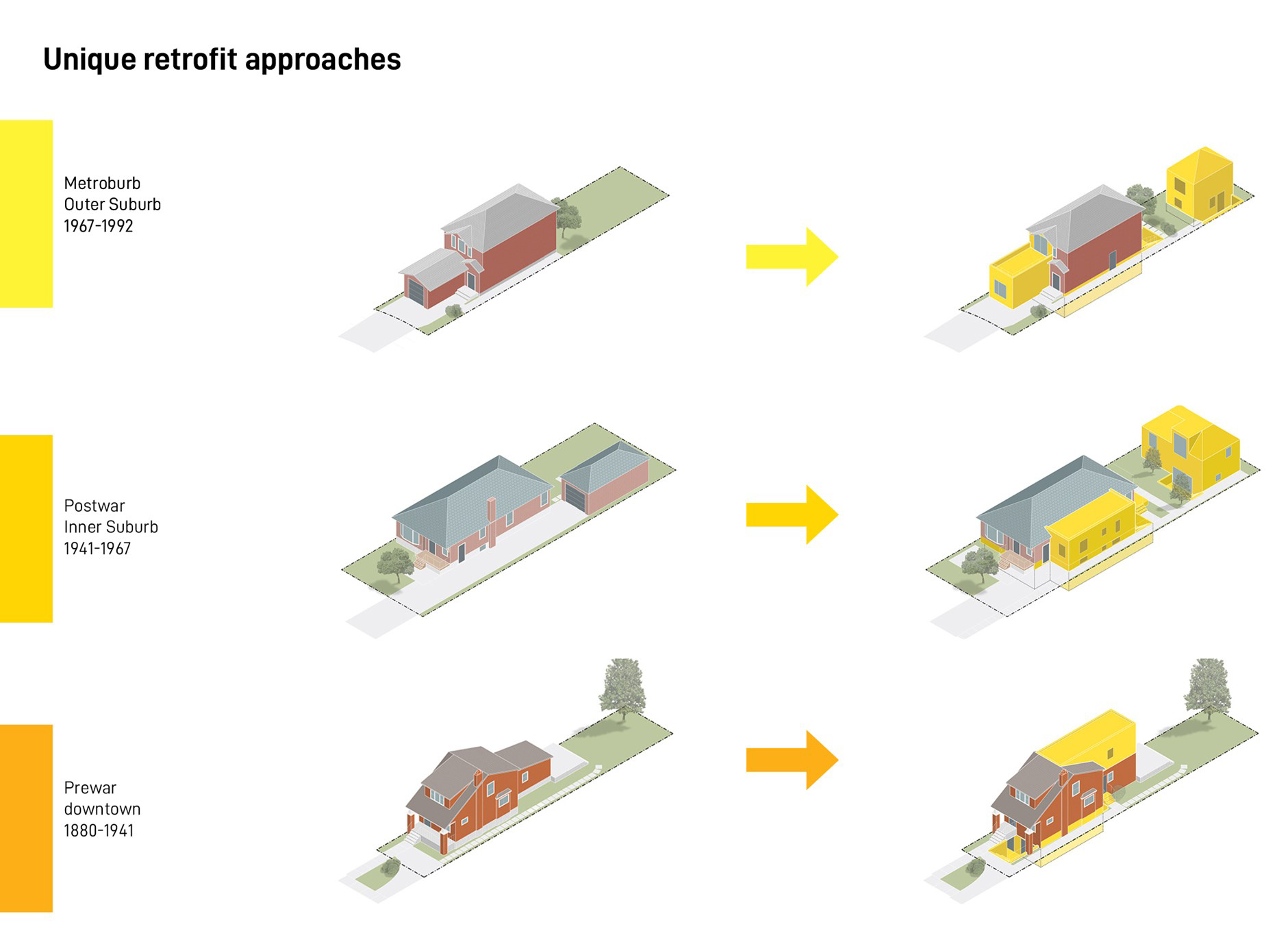

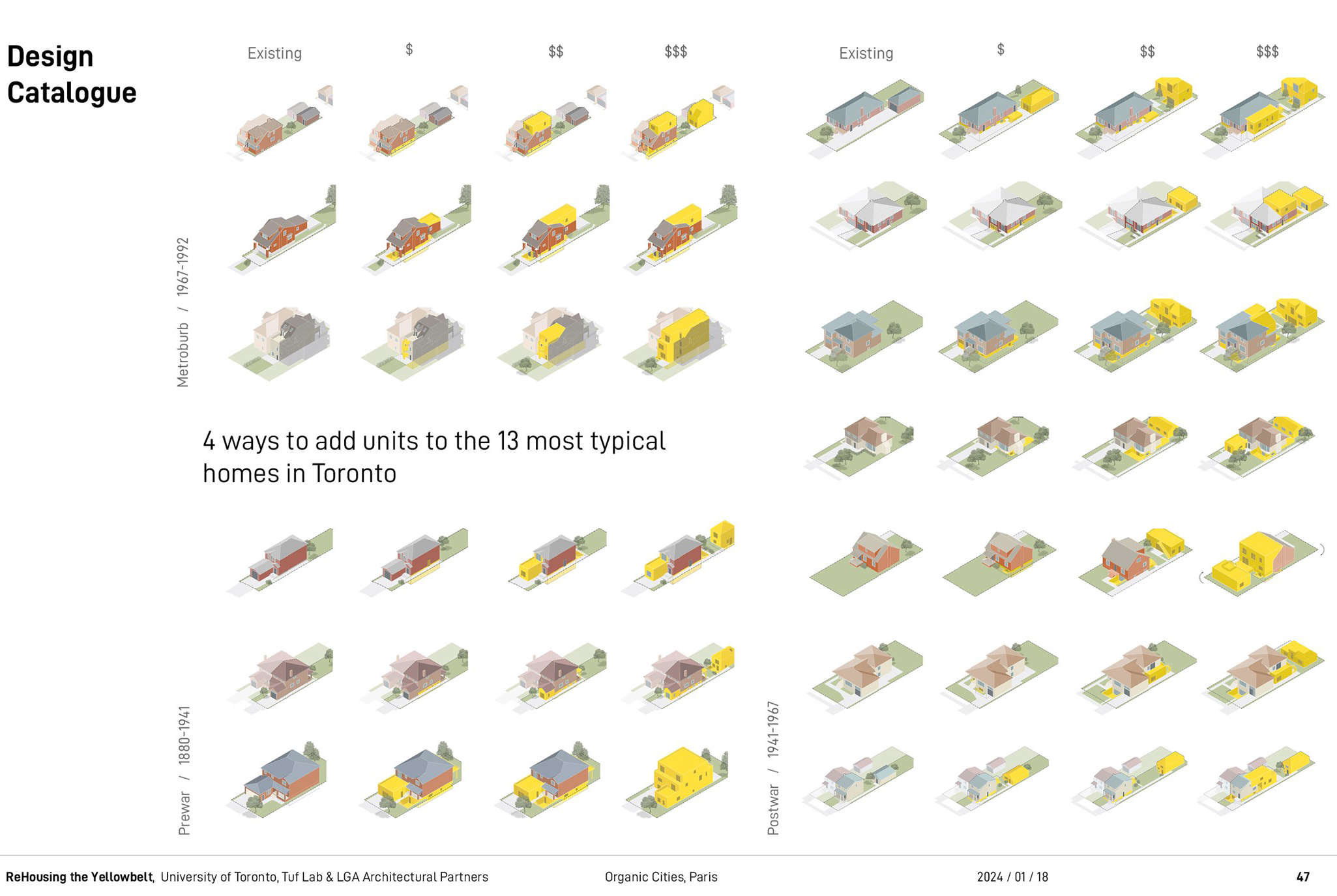

Here are 13 of the most typical homes in the Toronto region according to age of construction from the interwar and pre-war years to the post-war generation suburb to the metroburb or outer suburbs.

Different types of homes enable different kinds of unit creation. This set of drawings compares different ways of adding units that respond to different kinds of homes.

For example, the post-war suburban lot is rather large and therefore horizontal inexpensive additions can be made without having to build above. In the downtown, parcels are smaller, forcing landowners to build up to create more density.

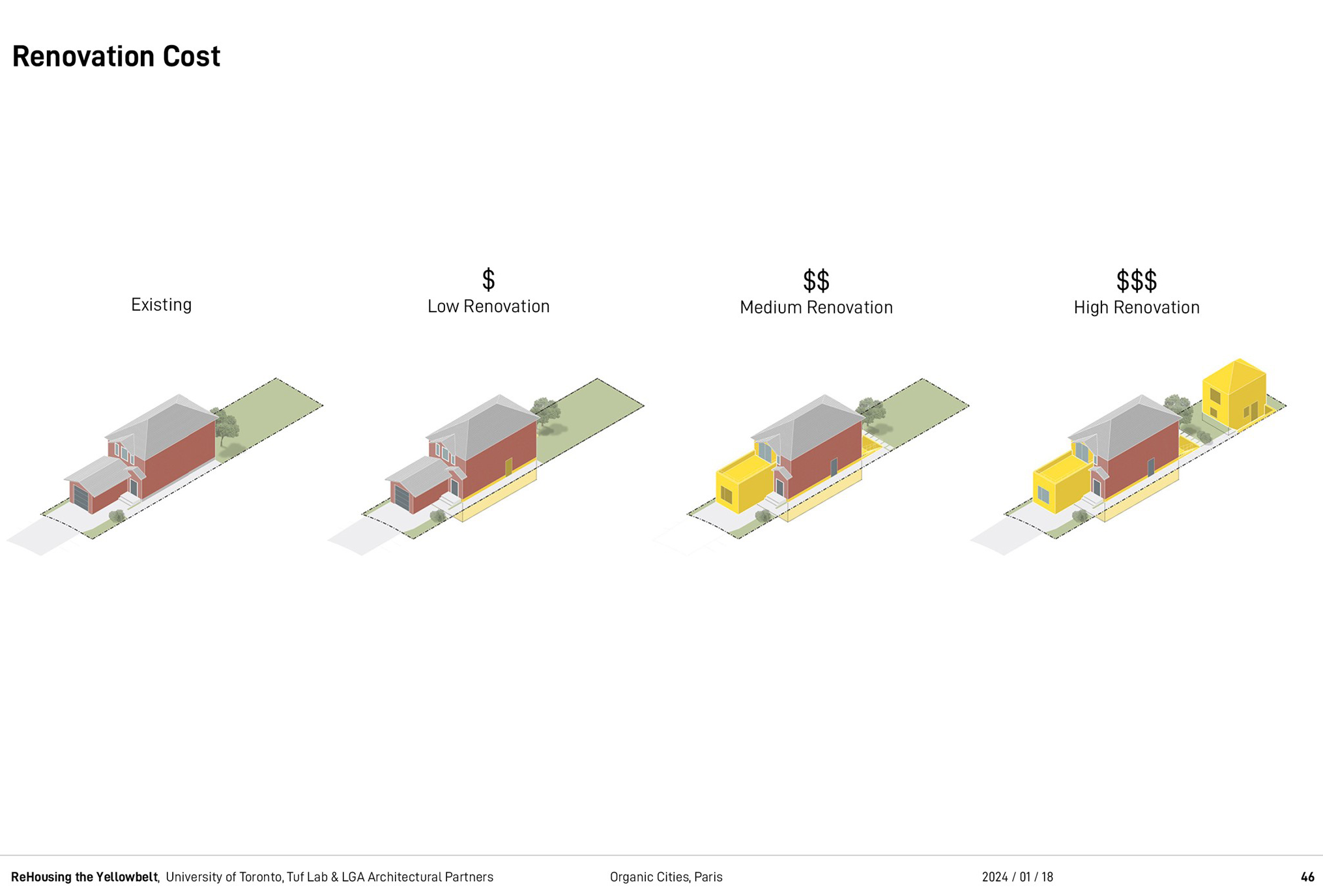

As part of the research, we looked at different costs of intervention ranging from small low-cost single basement conversions to higher renovations and higher costs, as shown here.

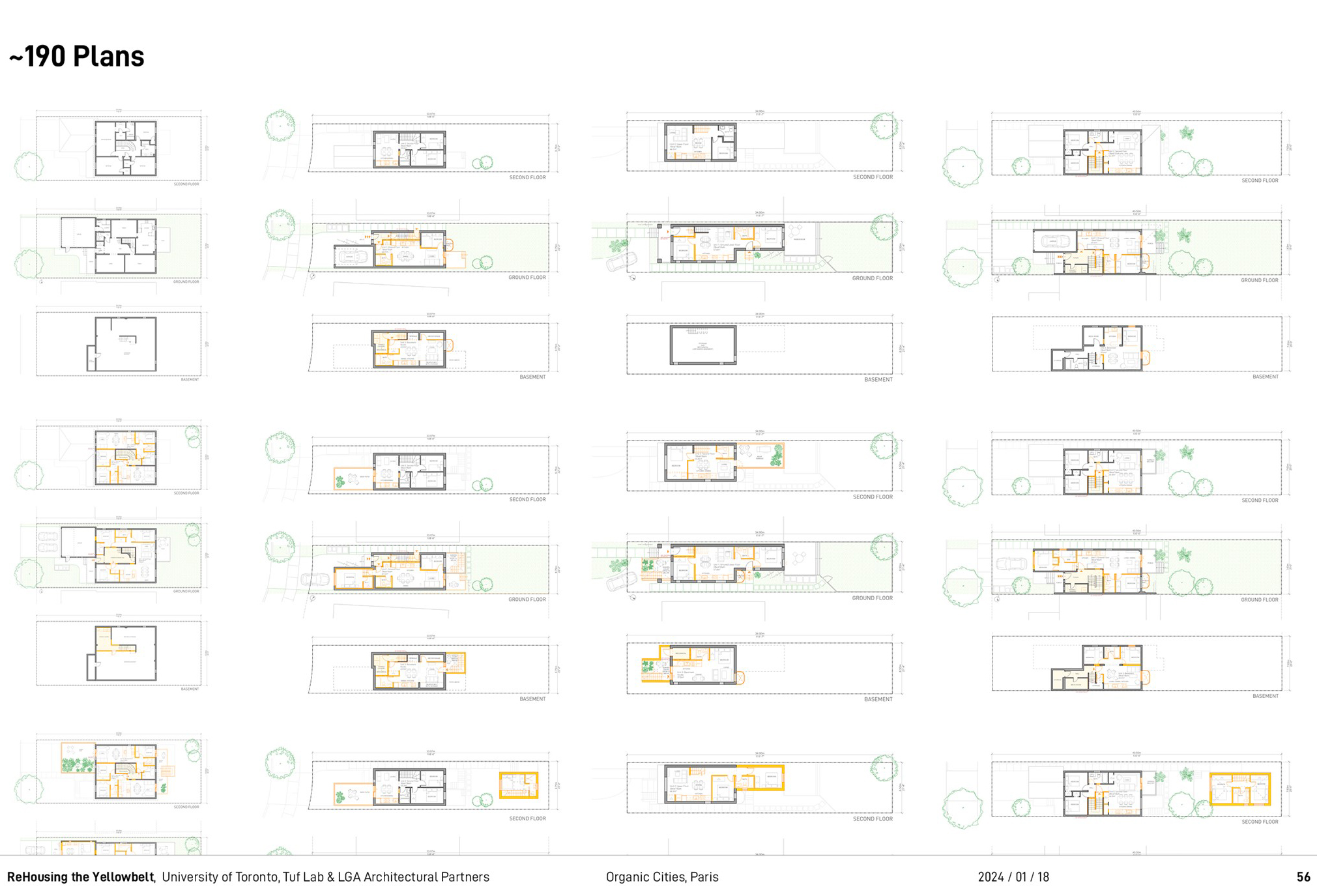

This housing catalog that we created cross-references cost to building type and develops a range of project types that people can access on our website. For each home type we designed a series of scenarios that show between one new unit to four new units. For each scenario we developed a set of plans, diagrams, and renderings, as you can see with these five images .

People often ask why we’re not showing more radical forms of density in these areas. Our response is that we wanted focus on projects that home owners could create. These small interventions are intended to be feasible for non-professionals.

Our online catalog offers 190 plans for free.

6 Conclusion

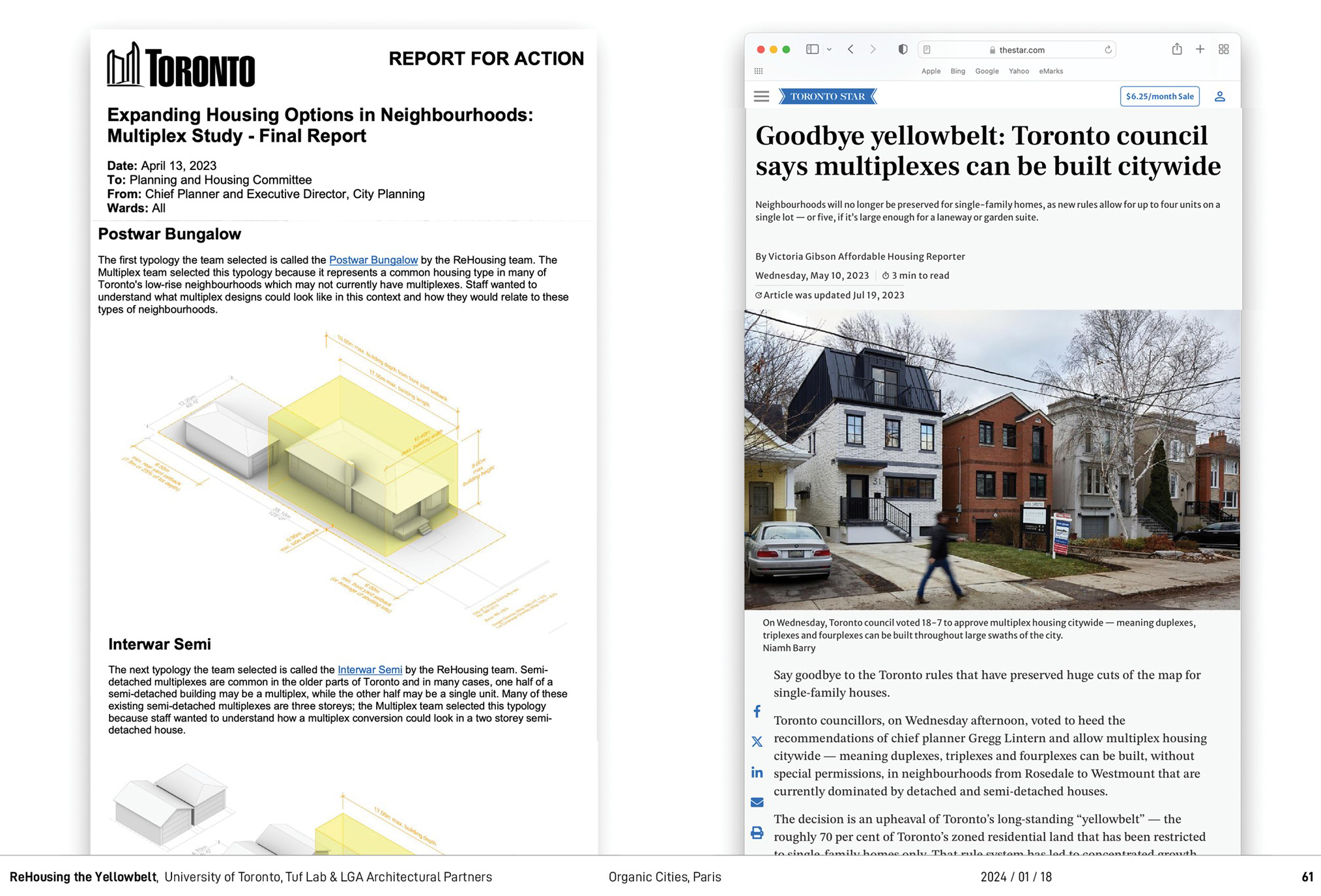

We have been commissioned by the City of Toronto in 2022 to help develop the Multiplex zoning policy for single family neighborhoods. The new zoning would allow up to four units per lot. They asked us to use our design catalogue to test out different zoning rules.

Our work was included in the policy change that was sent to and approved by city council. Citizens and residents are now allowed to have five units on a single lot — a fourplex plus a back-yard garden suite. This is a big deal in the context of Northern America where for the longest time, only one unit was allowed on these lots.

We were excited to participate in that policy change and are working with the city, now, on looking at six units per lot and actually on this next scale of development and trying to find ways of promoting small developers so not just homeowners but people who would make small apartments.

Réutilisation

Citation

@inproceedings{piper2024,

author = {Piper, Michael},

publisher = {Sciences Po \& Villes Vivantes},

title = {Opérer la densification douce des premières couronnes de la

métropole de Toronto},

date = {2024-01-18},

url = {https://papers.organiccities.co/operer-la-densi-cation-douce-des-premieres-couronnes-de-la-metropole-de-toronto.html},

langid = {fr}

}